Episodes of Death and Destruction - a recap of the Wasco County Geology Field Trip

/Trip Dates: July 7-9, 2024

Trip Leader: Clark Niewendorp

Article by Carol Hasenberg

Photos, unless noted otherwise, by Carol Hasenberg

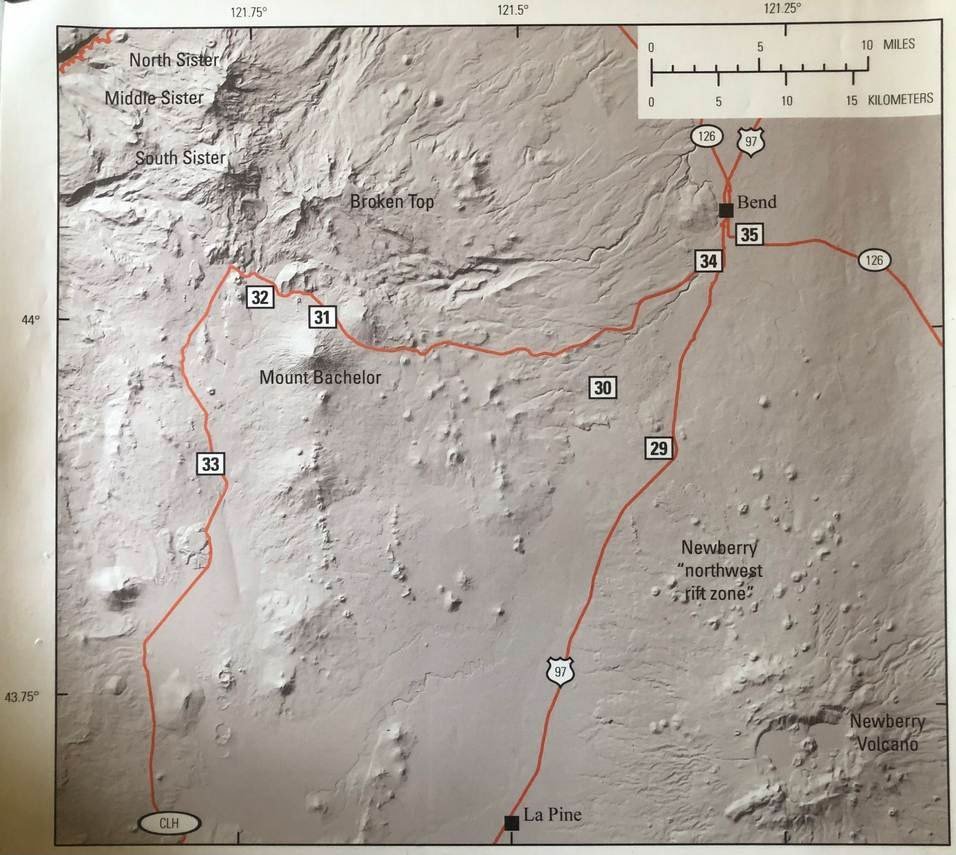

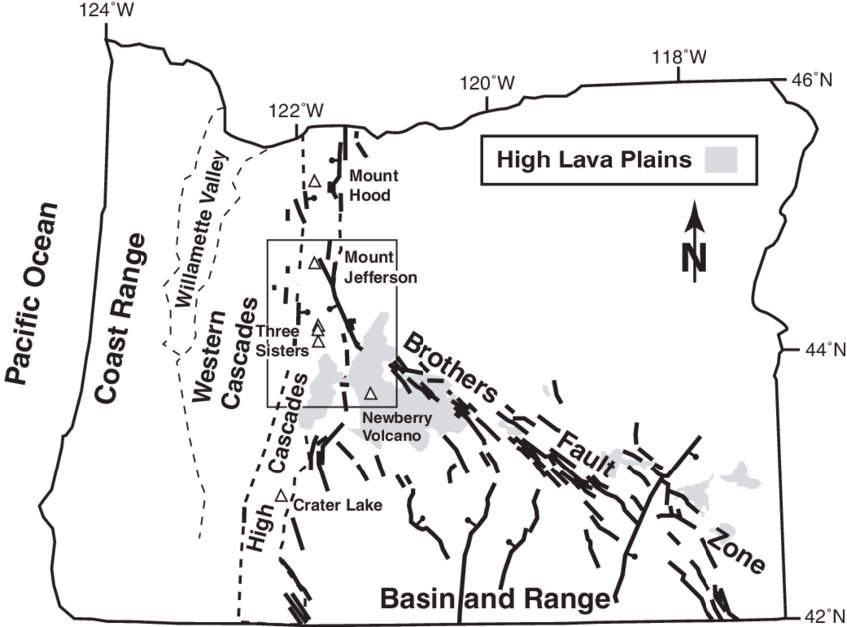

Reconnaissance Points for Wasco County Geology Field Trip. Note the uptilting of the bedrock platform bounded by the Tygh anticline.

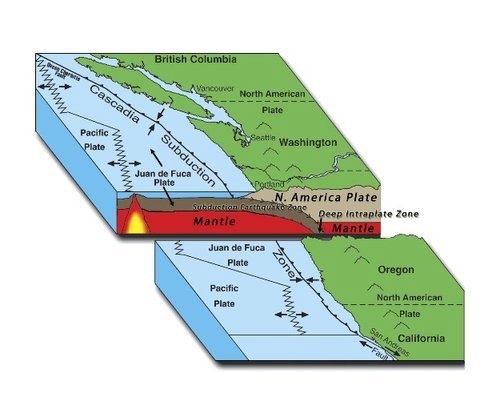

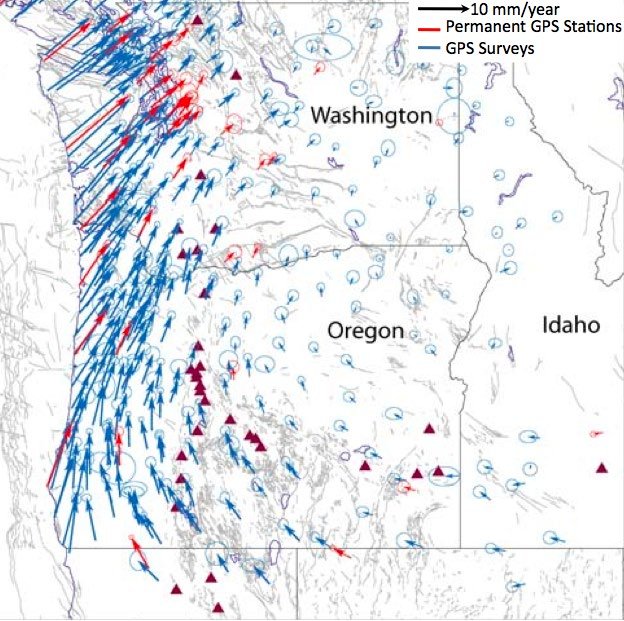

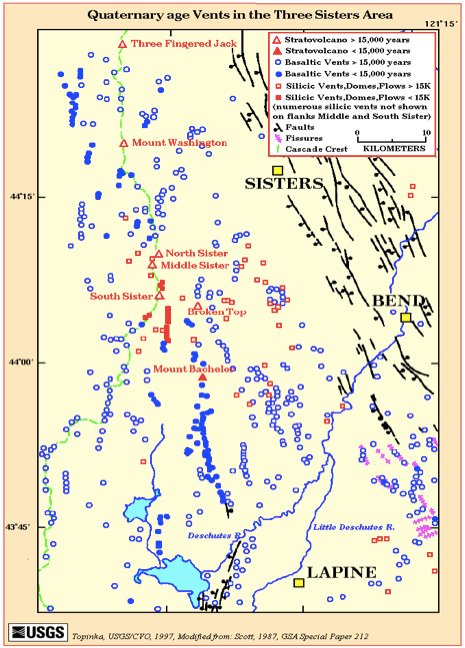

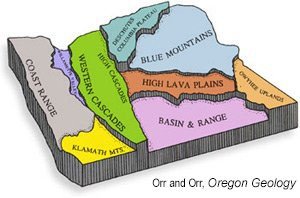

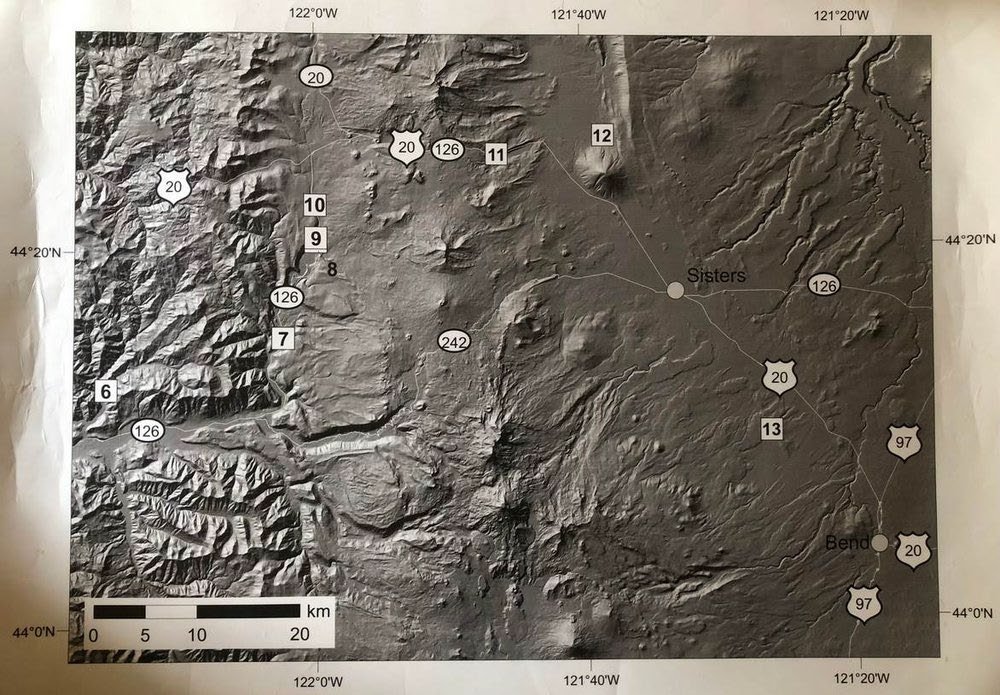

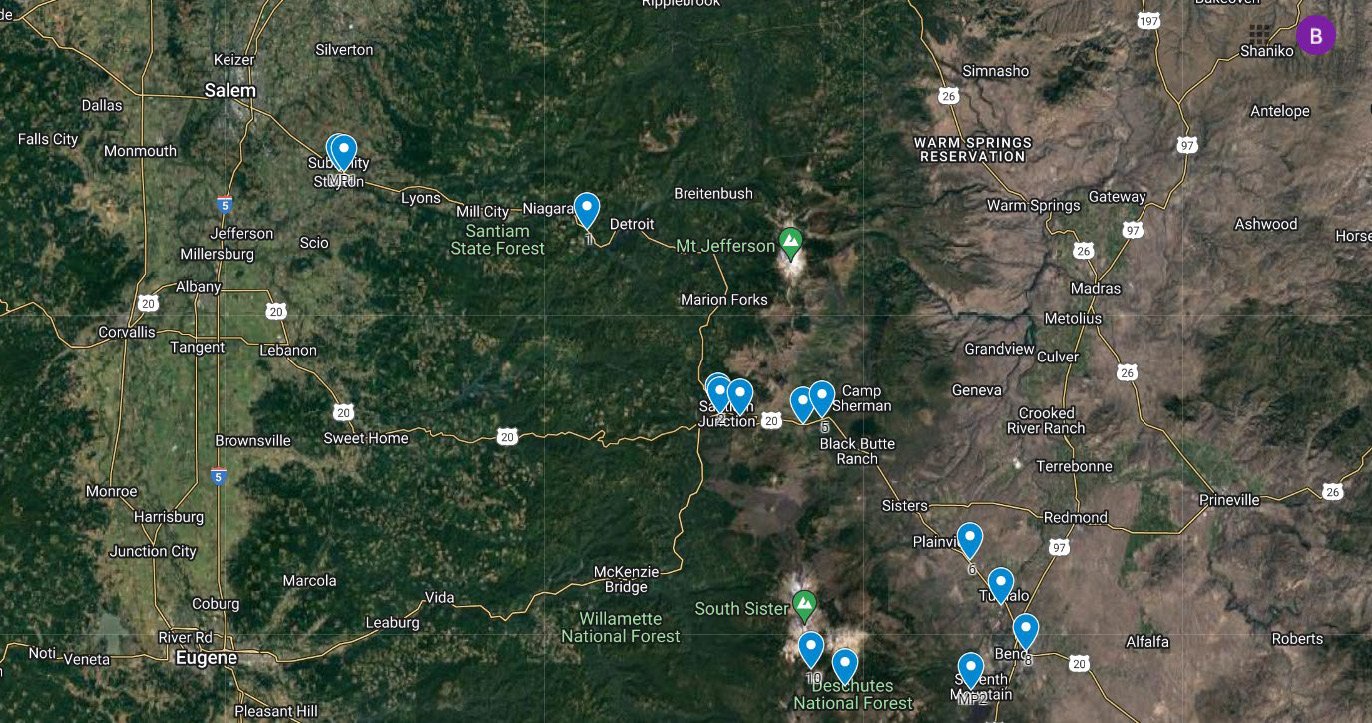

In the June 2024 field trip, GSOC participants were treated to explore some of the geological fieldwork and mapping done by Jason McClaughry and field trip leader and GSOC Past President Clark Niewendorp of DOGAMI over the years 2014-2020. The main subject of the field trip was volcanic materials that originated in the Mt. Hood area of the High Cascades and were deposited on the eastern flanks of these mountains in Wasco County between The Dalles and Tygh Valley from the Late Miocene onwards. All this volcanic material is underlain by a platform of Columbia River Basalt. Also, the group examined the effects of folding and faulting associated with the Yakima Fold and Thrust Belt. Late Pleistocene surficial deposits – notably wind-blown loess and megaflood sediments – completed the surface geology they saw in the area.

Day 1

The trip was based in The Dalles, and the group assembled in The Dalles’ Home Depot parking lot on Friday morning. At this location, the outcrops of lahar, or mudflow, and deposits of the Dalles Formation can be seen crowning the nearby ridge. The Dalles Formation is the late Miocene to early Pliocene (9-5 Ma.) collection of lava flows, pyroclastic flows, debris flows, and fluvial sediments deposited from activity to the west on the High Cascades volcanic arc. In general, much of the material from the Dalles Formation is light grey, and finely textured, which may be studded with larger clastic rock pieces. The focus of Day 1 was to familiarize the group with the Dalles Formation and similar-looking Missoula Flood deposits and explore the faulting, folding, and landslides that have reshaped the landscape since they were emplaced. Clark Niewendorp led the group at all of the Day 1 stops. He recounted that many samples had to be taken from the area covered in Day 1 to get a reasonable picture of the geology, and a lot of debate about the true nature of the stratigraphic structure.

Traveling a short distance to Stop 1 on Chenowith Loop Road, the group got a close-up view of this material. Niewendorp posed the question of how the mappers could distinguish between this light grey material and the Missoula flood deposits found in the area. A sparkly glint in the material hinted at an answer – this material contains a lot of glassy fragments. Mappers had samples sent in to verify the contents of each sort of material they encountered since many of the deposits of material here look similar to the naked eye. Another hint that the mappers were into the Dalles Formation (lahars and tuffs) was that birds (starlings and swallows) do not make holes for nests in banks of this material, perhaps due to its abrasiveness or its hardness. Conversely, birds love to nest in banks of Missoula flood deposits.

Quite a few faults crisscross the sediments southwest of The Dalles. At Stop 2, much farther up Chenowith Creek Road, the group examined breccia (i.e., broken rock) formed by the Chenowith Fault, trending from WSW to ENE. Fault breccia is created as the two sides of the faulted material grind by each other. It is material that is impervious to water, and that is why the gravel road just before the stop was wet and potholed from impounded water leaking onto the road.

The group backtracked to Stop 3 at the crossroads of Chenowith Creek and Browns Creek Roads. Along Browns Creek Road, the tan banks are pockmarked with bird’s nest cavities—aha! Some Missoula flood deposits! At an elevation of 505 feet, this deposit is well within the under-1000-foot elevation range of deposits from the floods. Next, the group went up the Browns Creek Valley, crossed the stream, and headed up to the top of Cherry Heights Ridge. Atop the ridge, the group had a panoramic view of the massive Government Flat landslide to the west, whose escarpment is in alignment with the Cherry Heights fault, trending from SE to NW. At the top of the slide, Niewendorp pointed to a large topple block. Mt. Adams peeks out above the ridge to the north. From there, the group headed to the lunch stop at Sorosis Park, located on the hill south of downtown The Dalles.

After a short repast in the oak-studded park, the group assembled at a nearby overlook to the city, Stop 5. To the west, below the ridge capped by The Dalles Formation, a large landslide is studded with trees and homes.

The group then headed up Mill Creek Road to a point where the Maupin Fault, trending NNW to SSE, crosses the Mill Creek valley. A dip in the ridge to the south indicates the fault area. The sediments to one side of the fault at Stop 6 are tuffaceous siltstone beds within the Dalles Formation.

Further up the creek, an anticline (barrel-shaped fold) terminates at the creek in a downward sinking nose. The Dalles Formation sediments and Columbia River Basalt are both folded in this structural feature. Traveling around the end of this feature to Stop 8, the group encountered some more fault breccia from the North Fork Fault Zone. This was the last stop on Day 1 of the trip.

Day 2

The activity of Day 2 was centered more to the east and south of that of Day 1. Day 2 focused on three things – (1) An unusual roadcut on US 197 at the top of the hill south of the bridge over the Columbia River, (2) Stratification of the Columbia River Basalts and The Dalles Formation on Five-Mile Road south of The Dalles, and (3) Following tuffs laid down by pyroclastic flows along Dufur Gap and Friend Roads to the point closest to their origin that can be found. The group was accompanied by GSOC President Julian Gray for this day of the trip.

The group assembled at Stop 9 on Day 2 at the crossroads of US 197 and US 30. Here is a classic roadcut through the Priest Rapids Member of the Wanapum Basalt (part of the Columbia River Basalt Group). The top half of the roadcut is a colonnade of basalt, and underneath that is a section of pillow basalt encased in palagonite.

Next, the group proceeded up the hill to the unusual roadcut, Stop 10, where PSU Emeritus Professor Scott Burns was waiting for them. Burns was well acquainted with the roadcut as an old student of his, David Cordero, discovered its significance and analyzed it for his master’s thesis in 1997. This roadcut contains several layers of paleosol (ancient soil) units with a thin layer of wind-blown loess at the top. Each layer represents a deposit of material which, over time, developed classic soil horizons within it over thousands of years’ time. The middle layer is around 600,000 years old. This was determined by two methods that corroborated themselves – particles of Dibekulewe Tuff originating from Mt. Adams in the layer that dates from that time and paleomagnetic reversal of the layers below the one containing the dated tephra. Cordero concluded after his painstaking analysis that all of the paleosols had been flood-deposited. Burns later revisited the site to do more research on the oldest of the paleosol layers (those older than 600,000 years), He found that there were 5 exposed paleosols in that area of the cut, all flood-deposited.

On the north end of the roadcut, the paleosols have been eroded away and are replaced by a massive deposit of flood material that is attributed to the Missoula floods. At 650 feet above sea level, this deposit is well within the range of Missoula Flood deposits in the area, which may be found up to about 1000 ft. Burns pointed out other details in the roadcut, including a clastic dike that cuts through the paleosol layers but not the loess at the top, a small fault, and details of the soil horizons and extent of the calcareous deposits in the paleosols. One of the most easily recognized horizons, and thus the number of paleosol layers is the Bk, or caliche, layer which develops in soils in arid regions.

The group then traveled south down the hill and turned west onto Five Mile Road. In a short distance, they encountered a quarry that had mined a massive wall of Columbia River Basalt, Stop 11. At the top of the quarry wall, Niewendorp pointed out the contact between the basalt and the Dalles Formation. This contact had many rounded boulders at the bottom of The Dalles Formation. The next stop was a few miles west of this site. At Stop 12, Niewendorp discussed the reverse grading (i.e., finer material at the bottom) of the lahar exposed in an erosion-resistant outcrop of the Dalles Formation. The group then headed for Friends of Dufur Park for a lunch break.

For stops 13-14, the group traveled south on Dufur Gap Road south of Dufur to Friend Road, which ran directly west towards the High Cascades foothills. Stops 15 and 16 were located on National Forest Roads, branching off of Friend Road in the foothills. Stops 13 and 15 traced the path of some block and ash flows that produced tuffs in the roadcut at Stop 13 and surface exposures at Stop 15. The group spent a while poring over the roadcut along Dufur Gap Road at Stop 13, a complex block and ash flow called Engineers Creek Tuff. The pyroclastic flows were concentrated in an ancient stream channel that was exposed in the roadcut. Niewendorp gave the group a little history lesson on Stop 14 at the old Friend School, where a train line once terminated that served farmers, ranchers, and loggers from The Dalles in the early 20th century.

The Tuff of Friend was the target of Stop 15 on a branch of the Camp Friend Road. Like the Engineers Creek Tuff of Stop 13, it contains chunks of dark glassy dacite and dacitic pumice clasts. The source to the west remains unknown and is probably buried. Four miles up the main road (Camp Friend/Jordan Creek/Cold Springs Roads), a large flow of dacite crowns the ridge. It has a porphyritic texture as it is studded with phenocrysts. The beautiful outcrop and scenery of Stop 15 ended Day 2 of the tour.

Day 3

For Day 3, the group traveled south across the block of Columbia River Basalt, which is the bedrock of this area, and over and down the south side of the Tygh Valley anticline. This topography was deformed after the Columbia River Basalt flowed by the tectonic forces that formed the Yakima Fold and Thrust Belt, as the Tygh Valley contains the same stratigraphic units of basalt at a lower elevation. Turning east onto Hwy 216, Sherars Bridge Hwy, the group arrived at the only scheduled Day 3 stop, the White River Falls State Park. This was an excellent scenic stop to view the interplay between the basalt bedrock and the vigorous flow of the White River, which originates on Mt. Hood, and observe the flora and fauna of the park. The ruins of a historic power station, one of the earliest in Oregon, can be seen below the falls.

The tour covered the northern section of Wasco County in regions that had recently been mapped by DOGAMI. The stratigraphy to the south of the mapped area is somewhat different than that to the north and is intriguing to explore. On the reconnaissance mission for the trip, Niewendorp and Carol Hasenberg drove along NF-27, NF-2710, Happy Ridge/Badger Creek Roads, and Victor/White River Crossing Roads, observing outcroppings of tuff, quarries of volcanic cinder cones with volcanic bombs, and lakebed sediments. This area, which is so close to Portland, might be an interesting study area for geology master’s students and a future GSOC field trip.