Charter GSOC member Lon Hancock was first to discover vertebrate fossils in the Oregon's Clarno Formation

/Lon Hancock, working at The Clarno Nut Beds.

by Viola L. Oberson

GSOC President 1984

Reprinted with permission from Oregon Geology, Oregon Dept. of Geology and Mineral Industries, December 1979.

Paleontologists the world over know of the work of Alonzo Wesley "Lon" Hancock (1884-1961). Professional men from the universities and museums of the world came to his door to study the fossils he found. He considered himself an amateur, attained no college degrees, and published no scientific papers, but the fossils his persistence enabled him to find have been the subjects of numerous papers, master's theses, and doctoral dissertations. And part of the geologic history of ancient Oregon has had to be rewritten because of his discoveries.

“When he retired after 35 years of carrying mail by horse cart and on foot for the U.S. Postal Service in Portland, he believed he had hiked as much on the hills of his beloved Clarno-John Day country as he had walked the sidewalks of Portland.”

Starting in the early 1930's, Lon Hancock combed the John Day-Clarno hills of north-central Oregon in his spare time, looking for vertebrate fossils in the Eocene Clarno Formation. At times he was accompanied by such scientists as Ralph Chaney, University of California; Chester Arnold, University of Michigan; Chester Stock, California Institute of Technology; Charles Falkenbach, American Museum of Natural History; Donald E. Savage, University of California at Berkeley; and Richard A. Scott and Jack Wolfe, U.S. Geological Survey.

Sometimes his search parties consisted of a few friends, and often he went with his wife Berrie, who would drive their car so he could concentrate on looking for outcrops on the hills or in roadcuts. When he retired after 35 years of carrying mail by horse cart and on foot for the U.S. Postal Service in Portland, he believed he had hiked as much on the hills of his beloved Clarno-John Day country as he had walked the sidewalks of Portland.

Tom Bones (Left) and Lon Hancock at work at the Clarno Nut Beds.

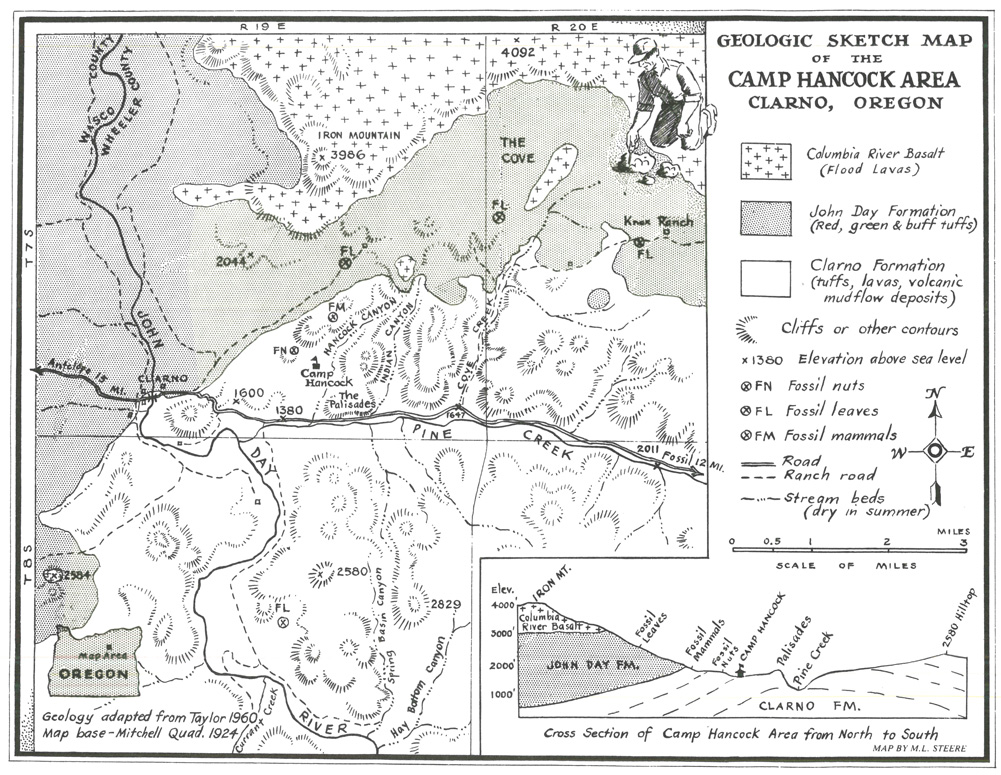

The Eocene Clarno Formation consists of andesite, mudflows, and tuffaceous sandstones, siltstones, and conglomerates (Oles and Enlows, 1971). It was named by John C. Merriam, who in 1898 led a University of California field party in the exploration of the John Day Basin. At that time, and for many years after, although numerous plant fossils were collected from the Clarno Formation, no vertebrate fossils were found. Thomas Condon (1910) wrote: "Just why the remains of these same Eocene mammals have not been found in eastern Oregon is one of our unsolved problems. Either the Shoshone region was cut off from the Wasatch region by intervening waters, or if these animals lived in Oregon, their remains may yet be found." Edwin T. Hodge (1941), University of Oregon, wrote: "The only fossils found in the Clarno are plants; no animal remains have been found." For many years, the search was on to find a bone!

In other parts of the world, geologic formations with the same fossil flora had yielded vertebrate fossils as well. Why the John Day Formation, stratigraphically just above the Clarno Formation, should be so rich in vertebrate fossils-and not the Clarno-was a question that challenged both professional and amateur paleontologists and geologists.

Lon Hancock in his home museum, showing fossil nuts, seeds, and leaves from the Clarno Nut Beds.

On May 28, 1938, Hancock received permission from State Superintendent of Parks S.H. Boardman to dig and collect fossils in John Day Fossil State Park. Together with a friend, Tom Bones, he made the first discoveries of agatized nuts and other fossilized fruits and seeds in what later became known as the Clarno Nut Beds. Since 1942, Tom Bones has devoted his studies entirely to this area, and OMSI recently published a paper on his work (Bones. 1979).

“Squeezed tightly against a fossilized walnut was a perfectly formed tooth! Here was proof that animals lived during the Eocene in Oregon.”

In 1952, a package of seeds and nuts sent from Hancock was examined by Richard A. Scott, then in London, together with Marjorie E.l. Chandler, Curator of the Department of Paleobotany at the British Museum. One pitted seed was identified as a new species of the same genus as a smaller "peach pit" specimen found in the London Clay. Scott wrote to Hancock: "Its relatives lived only in the Malay Peninsula and have never been found either living or fossil in America before-and this large specimen is over twice as large as any previously known species of this genus. If you would be willing to donate this specimen to the University of Michigan Museum, I would like to describe it as a new species, Paleophytocrene hancockii, if you don't object to the use of your name." Hancock answered promptly that he would be honored to lend his name to this new species, which was the first of several to carry his name. Large Clarno Nut Bed collections are now in the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C . and at the Visitors' Center, dedicated August 23, 1978, at the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument, on the former Cant Ranch, Dayville, Oregon. Most of the specimens were collected by Tom Bones.

Hancock continued his search for fossils and in September 1942 made a find that cleared up one aspect of Oregon's ancient history. His consuming dream had finally come true. Squeezed tightly against a fossilized walnut was a perfectly formed tooth! Here was proof that animals lived during the Eocene in Oregon.

Lon and Berrie hand carried this precious specimen to R.A. Stirton, University of California at Berkeley, who wrote in his 1944 identification monograph: "The only known fossil mammal tooth from the Clarno Formation of Oregon is a rhinoceros second lower premolar which was discovered near the Clarno Bridge on the east side of the John Day River ... in Wheeler County, Oregon. The specimen was found in a tuffaceous matrix bearing crystals of pyroxene and feldspar; many poorly preserved plants were also present. It was found by Mr. A. W. Hancock of Portland, Oregon, in September 1942 and was presented to the University of California Museum of Paleontology for description and preservation .... This, then, is the first specimen recorded outside of the Rocky Mountain area on this continent" (Stirton, 1944). This discovery of a Clarno Hyrachyus or rhinoceros tooth dated the Clarno Formation as middle Eocene (Stirton, 1944) and led to the discovery of the mammal beds.

In April 1954, Al McGuiness directed Hancock (to a spot a mile north of the Clarno Nut Beds where he had found some flat "stones" lying loose. Hancock recognized them as bones. He returned to the site five more times with either Murray Miller. Rudolph Erickson, Leo Simon. or Tom Bones, digging many test holes and finally finding some other bones, both small and large, this time in place. From these "new diggings" he later found many specimens that were added to his collection or sent encased in plaster of Paris to the University of Oregon Natural History Museum under the care of the director, J.A. Shotwell.

Part of Hancock's fossil collection, as arranged at OMSI by his wife Berrie. (Photo courtesy Delano Photographics)

One of these specimens, a tapir skull, was identified in 1963 and posthumously named for "the late A.W. Hancock, who was the first to discover a fossil mammal in the Clarno Formation" (Radinski, 1963). Radinsky. in his Yale University doctoral dissertation, identified one of Hancock's finds as the anterior part of a tapir skull with teeth and named it Colodon? hancocki;, sp. nov. It is expected that many other specimens that Lon collected will receive the name hancockii when all of the bones, teeth, skulls, and skeletal parts which he sent to the University of Oregon Natural History Museum or gave to OMSl have been identified. Many of the skulls that he collected are now on loan to the Department of Paleontology of the University of California at Berkeley, where Bruce Hansen is in charge of their care and identification.

Hancock found in the Clarno digs the largest fossil skull yet found west of the Rockies - that of the giant "Thunderbeast" Brontherium. Hancock unearthed rhinos, alligators, tiny camels, great cats, clawed horses, and horses tiny enough to have been carried under his arm or in his pocket. He also found parts of animals that had earlier been found only east of the Rockies and in Asia, among them Titanotherium, Amynodon, Vinlatherium, Hyrachyus, Chalicotherium, and Hyaenodon. As Phil Brogan wrote in the July 8, 1979, Oregonian: "Many other mammal finds have been made in the Clarno beds in recent years. They have linked Oregon's Clarno lands with the ancient continent of North America of the early Cenozoic Era."

hancock home museum

Lon Hancock was a most generous man. He shared his home museum with classes of grade school children twice a week during the school year. Over 15.000 children, including boy scouts, girl scouts, and campfire girls, and nearly as many high school and college students and adults came to his museum room, which was arranged according to geologic eras and back-grounded by Life magazine posters picturing the flora and fauna of each period. His generosity with his lifetime collection of mammal fossils, rocks. minerals, fossil leaves. nuts, and fruits was evidenced by his willingness to have it used forever as a learning tool. His case of fossil skulls and skeletal bones brought the first visitor to the old "Writing Room" in the historic Portland Hotel where OMSI's original office and display room were set up by John C. Stevens and managed by this author. In accordance with Hancock's wishes. His entire home museum collection was given to OMSI after his death.

Lon and Berrie had no children of their own, but their generosity and dedication to youth is marked by their establishment of an outdoor school in Lon's beloved Clarno land. They spent a year of weekends stockpiling rocks away from where the kitchen, dining room, and tents would be placed. Lon drew his plans well for this school whose textbooks he knew he could unfold for all who would come. No other man could hold so many spellbound wit h the story of the geologic ages as he did on the top of Red Hill with his "sermon on the mount."

Camp Hancock in its early days. (Photo courtesy Ed Bushby)

The spot he chose for the site of his first outdoor school later became known as Camp Hancock. It is now a place name on all Oregon maps and is described by Lewis L. McArthur in his book Oregon Geographic Names: "Camp Hancock, Wheeler County. Camp Hancock is a memorial to Lon W. Hancock, an amateur paleontologist and geologist. Hancock was born in Harrison, Arkansas in 1884. He left school at an early age and spent most of his adult life as a Post Office employee in Portland. He had an abounding interest in fossil hunting and during the 1945 he began taking young boys on outings in the Clarno area. These became more complex and in 1951 Lon and his wife look (fourteen boys and ten volunteer staff members for the first formal twelve day summer camp at Camp Hancock under the sponsorship of the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry. Interest grew apace and the early tent camp has grown to a modern, well-equipped facility. Hancock died in 1961and left his collection of more than 10,000 fossils and artifacts to OMSI" (McArthur, 1974, p. 111-112). Truly, as is inscribed on Lon's posthumously awarded OMSI trophy , he was "A devoted paleontologist who dedicated his future so that others could learn of the past."

About Author Viola Oberson

by Mary Lou Oberson)

As a child, I spent my weekends on geology field trips with my parents, Louis and Viola Oberson. During the 1950's, we caravanned with GSOC all over Oregon to study firsthand and explore. My mother had never really been interested in the sciences until she met and married my dad, who was a charter member of the GSOC, and taught high school science. They met at Roosevelt High School where my mother taught English and Journalism. It was not long before she realized her inner rock hound, began to enjoy the trips to various points of interest, and soon was hooked! From the early days in the 1940's, my mother began to take on a more active role in the Society by writing and directing skits for the annual picnic entertainment, becoming the newsletter editor, organizing the weekly lunches, and eventually becoming President in the Society's 50th year. Her journey with my dad from knowing little about geology in the beginning to becoming President is exemplified in several pieces of writing. She found a way to incorporate her training in journalism with her newfound knowledge of geology by writing about Lon Hancock, her friend, and their devotion to the creation of a Natural History Museum.