High School Teacher Emphasizes the Scientific Method in his Geoscience Class

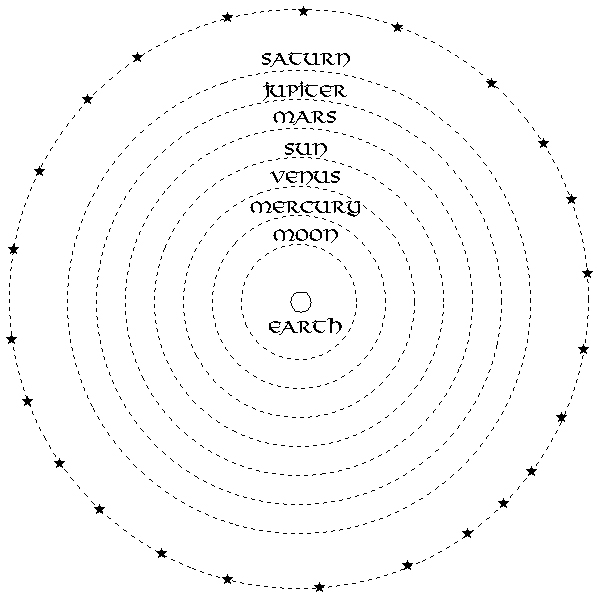

/Aristotle’s Earth-Centered Solar System Model (above) vs. Copernicus’ Heliocentric Solar System Model (below). Illustrations from www.bluffton.edu.

Synopsis of the GSOC Friday night lecture given on September 8, 2017, with speaker Frank Hladky, Oregon Registered Geologist and member of the National Association of Geoscience Teachers

by Carol Hasenberg

Frank Hladky, registered geologist who worked for DOGAMI (Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries) for 22 years, came to talk to GSOC about how he used his geological background to transform himself into a high school science teacher. He has been teaching high school in southern Oregon for over a dozen years now and is a member of the National Association of Geoscience Teachers.

His teaching is firmly rooted in the history of science and the geological sciences. His students study the work of Copernicus, Nicholas Steno, Robert Hooke, William Smith, James Hutton, Charles Lyell, and other giants of science. Through these the students also study the development of the principles of geology: the Law of Superposition, the Law of Original Horizontality, that fossils are the record of life on earth, and the concept of deep geologic time. Fossils as the indicators of geologic time, the evolution of life, uniformarianism vs. catastrophism, punctuated equilibrium are additional topics explored in Hladky’s class.

Hladky’s students study the process of developing a model, or simplification of reality, to explain natural phenomena and how the model is tested using the principles of the scientific method. The example Hladky used in the lecture was the Aristotle model of the solar system, with the earth at its center, which held sway for 1800 years until Copernicus came forth with a better explanation for the motions the planets exhibit in the sky in his solar-centered model. Hladky’s objective is to get the students to think for themselves and analyze the evidence. He reviews the Principle of Parsimony, or Occam's Razor, in which the simplest explanation is always preferred, or, the model which explains the most data with the least number of assumptions is better.

The topography of Table Rocks near Medford, Oregon . Created by ZabMilenko using Fireworks MX 2004, and information from the USGS National Map Seamless Server.

Armed with these analytical principals, Hladky then sets students to work in a real life geologic setting, and gather evidence to model how the landform evolved. He showed slides from a student project whose subject was the landform evolution of Upper and Lower Table Rocks, Castle Rock and Sams Valley near Medford. Upper Table Rock is capped by younger lavas with Eocene age rocks below. Cap rock consists of 7.1 million year old trachyandesite, higher in sodium and potassium than any other Cascades lavas. It is found for about 40 miles heading northeast from Medford, coming from a shield volcano at Olson Mountain. The horseshoe shapes of both Upper and Lower Table Rocks appear to mimic those of river bends.

Model 1 for the origin of Table Rocks is inverted topography with the horseshoe shapes following bends in the ancestral Rogue River.

Model 2 is a sheet flow model where bottom contact elevation varies, and the Table Rocks are not necessarily in the location of the ancestral Rogue River bed.

The first testing hypothesis Hladky’s students used is that if Model 1 is true, then the capping lava should all rest on similar age gravel, and as access was problematic this test was inconclusive. Another test is the scale of the features - do the width of the Table Rock features agree with the expected flow of the river? The actual features seem to be much bigger than the modern Rogue River, more like the scale of the modern Columbia River. Another test for Model 1 is that one would expect water altered lava at base of flow if it occurs in water, and it was not found. So, Hladky’s students concluded that Model 2 was more likely than Model 1.